The Topps Company, Inc. is a distributor of baseball cards originally packaged with gum as well as cards in other sports. For all practical purposes, Topps has enjoyed a monopoly on baseball cards for the last 50 years. And the business of baseball cards is not insignificant. For example, a Topps 1955 rookie card in mint condition featuring Roberto Clemente can be had on eBay for a little over $21,000.

But the Clemente card is going for chicken feed. The Topps 1952 rookie card for Mickey Mantle was auctioned this year for $5.2 million and the rarest of baseball cards (Honus Wagner from 1910 and originally free with a pack of cigarettes) was just auctioned for $6.6 million.

Which brings us to the business of saints. The Roman Catholic Church (and closely related churches like the Greek and the Russian Orthodox Church and the High Anglicans) have a monopoly on the creation of “saints.” The reason for this is that the other religions don’t really have any interest in recognizing “saints” because most of them believe that any faithful person who has died is already a “saint.” Indeed, most Protestant religions believe that one speaks directly to God and the Catholic notion that one approaches God through a patron is a theological non-starter and was one reason for the Reformation.

So, for example, you don’t find any Methodist Church named after a “saint” unless it’s a Saint from the New Testament like Peter, Paul, Mark, John or Stephen. Not so with Catholic institutions, all of which have religious names. In my area, we have a number of Catholic hospitals (Saint Joseph’s, Good Samaritan, Mercy, and Saint Agnes) as well as any number of Catholic parishes and schools named after Catholic “saints.”

It seems to me that Protestants miss out by not recognizing saints. Catholics, for instance, have saints for absolutely everything (and I mean everything to the point that one says “you’ve got to be kidding” but it turns out you’re not as there is even a patron saint for skiers and snowboarders, St. Bernard of Montjoux who spent decades in the Alps as a missionary). There is a Saint to pray to when you’re missing things (Saint Anthony) or for lost causes (Saint Jude). There are patron saints for professions (Saint Thomas More for lawyers, St. Luke for doctors, St. Thomas Aquinas for academics), for animals (Saint Francis of Assisi), for diseases of the throat (Saint Blaise), for travelers (St. Christopher), for immigrants (Saint Frances Xavier Cabrini) and for musicians (Saint Cecilia). And then there is the Virgin Mary who is not a saint but someone far greater and to whom you pray for her to intercede for you with God for just about anything.

The Virgin Mary, in Catholic tradition, has appeared mostly to children. There is Our Lady of Lourdes, Our Lady of Fatima, and Our Lady of Guadalupe. It seems that the Virgin Mary has appeared repeatedly throughout the world. And then there is the “Virgin of the Poor,” who appeared in 1933 in Banneux, Belgium to teenager Mariette Beco with a message. The Virgin of Banneux told Mariette that she had come to alleviate the suffering of the poor and broken-spirited. This was the first time that the Blessed Mother had appeared on behalf of the poor.

When 27 year old Father Al Schwartz reached South Korea in December of 1957, he did not speak the native language and he encountered a dystopian society that was real, not imagined. “It looked like the end of the world. Everywhere I looked I could see squalor, shacks, shanties, slums and refugees…” He was devoted to the Virgin of the Poor and had both visited Banneux and been ordained a priest a few months earlier. He had dreamed of being a foreign missionary since he was a young boy.

The fighting in the Korean War had ended on July 27, 1953 but it was among the most destructive conflicts of the modern era, with approximately 3 million war fatalities and a larger proportional civilian death toll than World War II. Virtually all of Korea’s major cities had been destroyed. There were at least 100,000 orphans in South Korea.

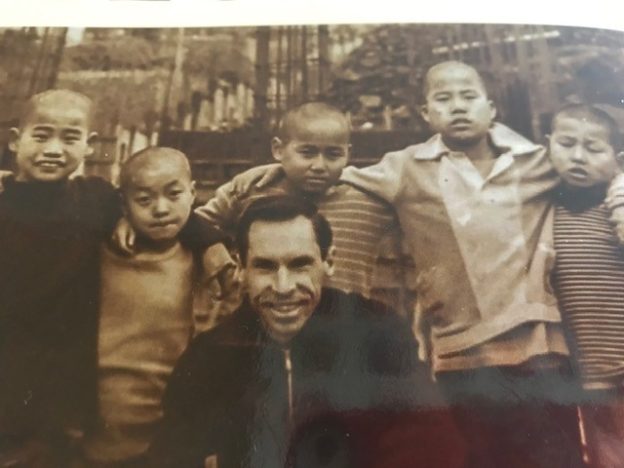

Father Al was bound by train for Busan, an impoverished town far south of Seoul. At one of the station stops, ten or so boys raced onto a train car and he recounted them as “scurrying under the seats and reaching between the legs of passengers for discarded pop bottles, scraps of food and cigarette butts. They pushed food hungrily down their mouths…..The boys were uniformly filthy and in rags, and their eyes burned with a fierce, scared, hunted-animal expression. When the conductor appeared in the doorway the boys scampered out of the car in near-panic carrying their spoils with them.”

The boys on the train had been one thing but what he found in Busan ultimately determined the course of his life. A few days after arriving he walked with a guide across a bridge to the island of Yeongdo into hundreds of mountainside hovels where there was tuberculosis, a scarcity of food, despair and illnesses brought on by the frigid winds blowing off the Sea of Japan. Fresh air was overwhelmed by the smell of disease, human waste and decaying garbage. He entered one 12’ by 6’ structure where 12 boys lived subsisting as rag pickers.

Within a year, it appeared that his missionary days were over. Dreadfully sick, he had to return to America to recuperate. While home, he went on an extended retreat to a Trappist Monastery in Virginia where he met a man named Gratian Meyer who owned a direct mail and marketing company. It was the beginning of a non-profit company called Korean Relief, Inc. which became so successful that some American bishops complained to the Vatican that funds were being diverted from their jurisdictions. Father Al had no idea of what he had begun. Entertainers, athletes and celebrities signed on to become sponsors of Korean Relief including Bing Crosby, Roger Staubach, Willie Stargell, Jonas Salk, M.D., Phyllis Diller, Ed McMahon, Mamie Eisenhower and Rose Kennedy.

Father Al had recovered his health and now had the wherewithal to help the “starving and the silent” in Busan and throughout South Korea. He didn’t return to his modest rectory in Busan but instead moved into a one room mud hut that lacked electricity, running water and plumbing but was just like the homes of his destitute parishioners and where they would feel comfortable visiting.

And the money poured in and with it began the construction of free sanitariums, free hospitals to aid the sick; then Boystown and Girlstown to house and educate all the orphans; developmentally disabled facilities and shelters for the homeless. The money kept coming. And, so too, did the construction of new and better facilities.

But the money would’ve been useless without his creation of an order of nuns known as the Sisters of Mary. The Sisters were the foot soldiers to staff the sanitariums, the hospitals, the orphanages and the other facilities. They too were drawn from Korea’s poor and were tasked with caring for those who were also poor.

It did not end in Korea. It was replicated in the Philippines and then, as Father Al was dying from Lou Gehrig’s disease, it was started again in Mexico. He died in 1992 but the Sisters of Mary, led by Father Al’s chosen designee Korean born Sister Margie Cheong, carried on for the Virgin of the Poor. There are now also free boarding schools for poor children in Guatemala, Brazil, Honduras and Tanzania.

There are three successive stages to becoming a saint in the Catholic Church: the first is Servant of God, the second is Venerable and the third is Blessed. Before being declared a saint, two miracles must be attributed to that person.

In 2015, Father Al became the Venerable Aloysius Schwartz.

Maybe Catholics go overboard when it comes to saints. But then, maybe not. It is important to recognize that there are saints among us.